|

|

|

|

New York Times - January 8, 2001

GETTING THE MESSAGE FROM 'ECO-TERRORISTS'

By DAN BARRY and AL BAKER

Earth Liberation Front claimed responsibility for fires in a Long Island subdivision late last month. The group began at a gathering of members of Earth First, an environmental group, in England in the early 1990's. [photo by Maxine Hicks for The New York Times] |

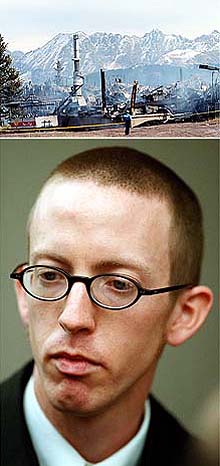

After a series of fires did $12 million in damage to a Vail, Colo., ski-lift operation in 1998, top, Craig Rosebraugh, left, ELF's publicist, said that the development was encroaching on a habitat for lynx. [Photographs by The Associated Press] |

MOUNT SINAI, N.Y., Jan. 5 -- The arson committed at the upscale subdivision being built on old farmland here, just off Route 25A in eastern Long Island, will never serve as a sophisticated model for the crime. The fires that torched three nearly completed houses were all ignited by birthday candles that had been attached to the handles of plastic jugs filled with gasoline.

And the messages spray-painted on another house in the subdivision that snowy, Dec. 30 morning did not seem particularly auspicious either: "ELF" "Stop Urban Sprawl." "If You Build It We Will Burn It." And, finally, "Burn the Rich."

But if the ELF acronym is mostly unfamiliar on the East Coast, it has long been a reference point in the Pacific Northwest for illegal and extreme environmental activism that law enforcement officials call eco-terrorism. It stands for Earth Liberation Front, a movement structured so loosely that trying to get a handle on it is like trying to grab a fistful of water.

For several years the people who claim allegiance to the group ELF and its partner in activism, the Animal Liberation Front, have taken responsibility for an underground campaign of destruction and fire against those they see as the earth's enemies: lumber and construction industries, mink and fox farmers, bioengineering companies and laboratories that do tests on animals. For ELF and ALF, they all represent base capitalism.

With a lanky vegan in Portland, Ore., acting as its publicist ÷÷ although he says he merely shares the information forwarded to him through means he declines to reveal ÷÷ the group boasts of what it considers to be nonviolent destruction, and provides a running cost estimate of the damage wrought, now at nearly $37 million. That total includes the $80,000 in damage done in Mount Sinai, and some big-ticket destruction as well, including the $12 million arson at a new ski resort in Vail, Colo., in 1998, and the $1 million arson at a lumber company's office in Monmouth, Ore., in 1999.

Although ELF has taken credit for acts of destruction elsewhere in the country, from the burning of a luxury home on the lip of a national forest in Indiana to the sabotage of a highway construction site in Louisiana, it has largely been associated with the West. But the Mount Sinai fires, along with several smaller fires last month and the uprooting of a cornfield at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory last summer, have brought its message and notoriety to the quickly vanishing farmlands of Long Island and to the media market of New York.

The day after the Mount Sinai fires, ELF issued a news release that included a local angle. It said the arson, for which it took full responsibility, was partly done to show support for Andrew Stepanian, an animal-rights activist from the affluent Long Island community of Lloyd Neck. Mr. Stepanian was recently convicted of throwing a brick through the display windows of a fur store in Huntington.

This morning, just before he was sentenced to 90 days in jail in Suffolk County Court in Riverhead, Mr. Stepanian and about two dozen supporters stood outside the courtroom and expressed admiration for the ideology of ELF They repeated the group's slogans and railed against "urban sprawl," but none admitted to being an "elf," as ELF members like to refer to themselves.

"I think what they did is a wonderful thing," said Mr. Stepanian, 22. But, he added, "we have no idea who they are."

Neither, it seems, do the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the United States Forest Service or any of the other federal, state and local law enforcement agencies that have tried for several years to stop the movement and arrest the masterminds ÷÷ that is, if there are masterminds.

"Absolutely, there's frustration," said Kevin Favreau, the F.B.I.'s domestic-terrorism supervisor in Portland, which comes as close as anyplace to being the base of the amorphous group. "But people always said the F.B.I. wouldn't infiltrate the Mafia, and we did. They said we wouldn't infiltrate the K.G.B., and we did. Is it harder than your average criminal group? Yes, it is. It's not a group you can put your fingers on."

Then again, he added, "Maybe law enforcement will start getting lucky."

But Craig Rosebraugh, the publicist in Portland, said he doubted that would happen. "There's no central leadership where they can go and knock off the top guy and it will be defunct," he said. "It operates on an ideology."

He described the movement as a series of cells across the country with no chain of command and no membership roll, a structure that supporters liken to that of the French Resistance and the African National Congress. There is only a shared philosophy, he said, in taking aim at "anyone who is destroying the environment for the sake of profit."

Because he is the spokesman for ELF, Mr. Rosebraugh's pale, bespectacled face is the only one attached to the movement, even though he says he is a supporter but not a member. As a result, federal officials have raided his home, seized his computer and placed him before a grand jury investigating ELF and ALF activities. Simply put, they want to know the identities of those who keep him abreast of what ELF is doing, and the means by which they do so.

Mr. Rosebraugh, 28, has refused to cooperate with the authorities, while at the same time cultivating an air of mystery about himself and the movement. When asked how he receives the information he disseminates, he said, "I never disclose the type of communication." And when asked whether a reporter could talk to active members, he said: "The people don't want to be known to the public. They want to stay free to continue doing the action."

The movement known as the Earth Liberation Front began at a gathering of members belonging to Earth First, an environmental group, in England in the early 1990's. Some people "thought that the movement didn't go far enough, that it didn't take radical or strong enough actions," said Jim Flynn, who works for the Earth First Journal. So they began ELF, which for a while did little more than encourage people to celebrate Halloween by vandalizing bulldozers and mining equipment.

By 1997, ELF had established a presence in the United States, and formed an alliance with the Animal Liberation Front. In November of that year, with Mr. Rosebraugh as its conduit, the alliance announced that it had freed 600 wild horses and burros from a corral in Burns, Ore., and then had torched an adjacent building.

But the movement's arson attack in Vail, in October 1998, earned it the full attention of the country ÷÷ and of the F.B.I. A series of early-morning fires destroyed several buildings of a ski-lift operation, causing more than $12 million in damage in what remains the country's most costly act of eco-terrorism. Mr. Rosebraugh said at the time that the development was encroaching on a habitat for lynx, adding of the arson, "As long as it doesn't harm human lives, we approve."

They claimed responsibility, and law enforcement agencies generally agreed, for a series of other actions: In Hermansville, Mich., holes were cut in the fence of a mink ranch, freeing about 5,000 mink. In Monmouth, Ore., offices of the Boise Cascade Corporation lumber company were destroyed. In Lansing, Mich., the genetic engineering research offices at Michigan State University were trashed and burned. In Niwot, Colo., a fire was set to a $2.4 million home under construction.

For all the emphasis that Mr. Rosebraugh gives to the loose, cell-like structure of ELF, there is a band of investigators who suspect that the movement has a small cohesive unit.

"From the activity that we've observed here, it appears that the core group of ELF is very small," said Bill Wasley, the director of law enforcement for the United States Forest Service, which is investigating the extensive vandalism done to its biotechnology research station in Rhinelander, Wis., last year. "They will attract local folks for specific activities and then go away. But it's very difficult to identify the total identity of the group."

Ron Arnold, the executive vice president of the Center for the Defense of Free Enterprise, a nonprofit agency in Bellevue, Wash., said that after researching ELF, he believes it operates as a "nomadic action group." For example, he said, a car with a couple of ELF members might leave Spokane, Wash., and drive across the country, stopping to drop off and pick up sympathizers along the way.

"You'll see these little crimes, bing-bing-bing, like ripples in a pond," he said. "This is a pattern we've seen time and again."

Teresa Platt, the director of the Fur Commission USA, which represents the interests of mink and fox farmers, generally agreed. "I don't think it's a large group; I think it's very mobile," she said. "The pattern is that it will quiet down in New York, and you will forget, and you will lose your political momentum. If they kept it up, your city wouldn't stand for it. But they move on."

Mr. Favreau, of the F.B.I. office in Portland, said the government's concern went beyond the damage done to buildings; it has to do with the dynamics of extremist organizations and the types of people they may attract. For example, he said, in 1999 some animal rights extremists, though not linked to the ALF, mailed razor-rigged letters, designed to cut fingers, to fur industry officials and scientists conducting experiments with animals.

"You start out with a large group that believes the same thing, and then it gets smaller and smaller and smaller," he said. "Ultimately, the type of thing we're trying to avoid is the lone guy who takes it to the furthest extreme."

But Mr. Rosebraugh maintained that ELF remains committed to nonviolence. "In the history of ELF, both in the United States and abroad, there have been no injuries to human life," he said. "The people take precautions so that no one gets hurt and their actions speak for themselves."

In fact, in a news release that immediately followed the fires here in Mount Sinai, the arsonists said they had made sure that no one was in the houses at the time the fires were set, and had even moved a propane tank out of the way. After apologizing for disrupting the firefighters' sleep, they added, "We encourage all citizens to donate generous contributions this year to your local volunteer firefighters."

Those sentiments did little to ease the mind of an assistant fire chief. "What if a fireman fell through the floor?" he asked. "There are just a multitude of ways that someone can get hurt like this."

The firefighter insisted on anonymity out of concern for his safety, explaining, "I don't know who these people are and how radical they are."

Email us with questions or comments about this web site.

All pages on this website are ©1999-2006, American Land Rights Association. Permission is granted to use any and all information herein, as long as credit is given to ALRA