|

|

|

|

Anger in Appalachia

page 2

Researchers Fighting to Open Records on 1930s Shenandoah Park Resettlement

By Leef Smith

Washington Post Staff Writer

Monday, March 6, 2000; Page B01

(Continued from previous page)

Engle dismisses Woodward's claim, noting that he has been critical of the resettlement himself and that he has called the government's actions "deplorable." And he insists he wants to open the archives as quickly as possible. "I am not trying to whitewash history. Frankly, I could sign the petition [to reopen the archives] myself," he said. "The park staff are not happy the archives are not open."

Over the years, several scholarly texts have been published on the resettlement. Woodward said his book will be different, focusing on the people who suffered the ordeal. Time is crucial to him because every year their number grows smaller.

Woodward grew up listening to the tales of his grandfather and other relatives, and he feels compelled to pass on their stories, from their European origins to their arrival in Virginia in the 1700s and their eviction from the mountain.

Like many such families, the Woodwards settled into pioneer life, raising just enough food for themselves and a few animals. They had no electricity, phone, running water or privy.

|

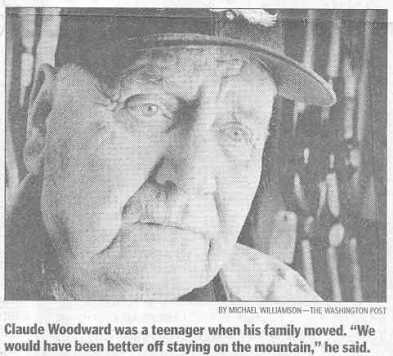

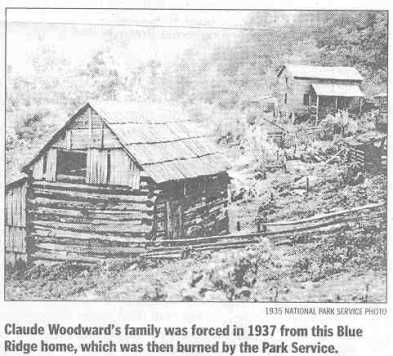

At the time of the evictions, the government portrayed the mountain people as poor, ignorant moonshiners who benefited from relocation, historians said. In fact, they said the families represented a range of economic classes: A few lived in large homes with electricity and phones, cars were not unheard of, most children went to school and most adults could read and write. In 1938 the government moved Woodward's grandparents and five children off Haywood Mountain to a farm near Madison. They were resettled in a four-room cottage on 40 acres, with a barn and a chicken coop. The catch was a mortgage and responsibilities they'd never known before. In debt, the family lost its second home in 1946. Claude A. Woodward, Harold's second cousin and the oldest of 12, was 14 when his branch of the family was forced from the mountain and resettled in two houses in Wolftown. Despite the space and relative luxury, they were miserable, said Claude, now 75. "We would have been better off staying on the mountain. It was so hard to adjust. My granddaddy never got over it. It hurt bad." Since the park's archive was closed three years ago, a few people other than Engle have been granted access, among them an archaeologist on contract with the park and a mapmaker who threatened to get his congressman involved if he were kept away. |

"It's not cricket that you can withhold public information paid for by taxes," said mapmaker Eugene Scheel, whose work has appeared in The Washington Post. "It's creating rather bad blood."

That's what led Jack and Carolyn Reeder, husband-and-wife authors who have published several books about the Blue Ridge and its people, to spearhead the petition drive to reopen the archive, or at least those documents--some 200,000--that have been catalogued so far.

Engle says he'd like to do that but won't. "It's a vicious cycle. If I open to the public, I can't be cataloging, and then we never get anywhere. We need the staff, and Park Service budgets are not very cooperative on that issue right now." So far, he said, nearly $500,000 has been dedicated to cataloging and storing the collection.

Cathryn Knupfer of the Rappahannock Historical Society said: "There are a good many people whose land was part of the park" who are upset they can't see the records. "It's really not fair they should have to [relive] the trauma."

By 1937 most of the people were gone from the mountains. The government let the elderly stay and live out their years there if they so chose. The last of them died in 1976.

Today, thick vegetation grows where cabins once stood, and weekend hikers climb the steep, rocky slopes. Walking up Haywood Mountain on a muddy footpath one recent afternoon, Harold Woodward veered into the brush, stopping just short of the crumbled remains of his great-uncle Nebraska Woodward's two-story cabin. Tourists pass by the site regularly, he said, but few stop to consider what people had to give up for the park.

"I'm not trying to grind any axes," he said. "I just want to tell the truth."

Email us with questions or comments about this web site.

All pages on this website are ©1999-2006, American Land Rights Association. Permission is granted to use any and all information herein, as long as credit is given to ALRA.